Review | SYNERGY: Tony Tuckson – drawing into painting

by Saskia Beudel • ABR Arts • 05 May 2023

I bump into two friends at the opening of SYNERGY and we peer into Tony Tuckson’s works, finding allegiances with and hints of other artists: the red, black, and white palette of Philip Guston; Ian Fairweather’s shallow space and densely patterned linework hovering between figuration and abstraction; Cy Twombly’s intricate, repetitive gestures; the torn edge of a calligraphic Robert Motherwell brushstroke in fluid black paint. Despite this pictorial conversation with other artists, the works don’t come across as derivative; they look and feel like a Tony Tuckson, which is quite an astonishing feat.

The romance of Tuckson’s story is well known. In the 1950s and 1960s, his position as Deputy Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales eclipsed his life as an artist. Not wanting to create any conflict of interest with his role as curator of Australian art, Tuckson went underground with his own painting. Away from the pressures of commercial galleries, curatorial interests and the public gaze, he produced a large body of work.

In 1970, at the age of forty-nine, he held his first solo exhibition. According to Margaret Tuckson, his wife, he finally decided to exhibit because their house was too small for him to be able to look at them critically on the walls. ‘He had no thought of selling them, or whether anybody else would like them. He wanted to see them up,’ she said in a 1979 interview with James Gleeson. Also, by 1970, he had become curator of ‘primitive’ rather than Australian art – alleviating his ethical dilemma.

A second solo exhibition followed in 1973 containing twenty-two of the large late works he became renowned for. ‘He was promptly recognized as probably Australia’s best Abstract Expressionist,’ writes an early champion of Tuckson’s work, Daniel Thomas.

This achievement might seem belated in art-historical terms. By 1973, the international art world had moved on from abstract expressionism. The 1960s had ushered in pop art, minimalism, conceptual, performance and land art. But this misses the intriguing question of Tuckson’s very private compulsion to make art regardless.

Just a few months after his breakthrough show, Tuckson died of cancer at the age of fifty-two, leaving behind many hundreds of untitled and undated paintings and drawings. It is from this vast archive that the Drill Hall Gallery now presents a rich selection of drawings never shown in public before.

‘When Tony’s son Michael Tuckson told us we could help ourselves and raid the plan chest, we thought we’d be panning for gold to find a few little glimmers of greatness. The residues passed over for earlier exhibitions,’ says Terence Maloon. ‘Instead, we discovered an abundance of wonderful things.’ Fellow curator Tony Oates elaborates. ‘We started with a drawer labelled “Abstracts” because we wanted to see a lineage in the works. We were about six or seven drawings in when we realised that these were not simply warm-up exercises to arrive at a painting.’

The lexicon developed in these drawings underpins SYNERGY. Whole series of the newly framed works remain undated; and yet there is a chronological flow. Clustered at the front of the gallery are early figurative works that pay tribute to Matisse, Picasso, and Dubuffet. From here, there is a process of dematerialisation. Figurative motifs such as the female nude, dancing figures, the laid table of a domestic interior, or two figures consorting around a cocktail shaker subside into faint vestiges of formal compositional shapes in the more abstract works. The materiality of gesture takes over: the making of marks in symbiosis with the surfaces that hold them.

In one of my favourite series, the drawings take on the pared-back simplicity and radiance of the late paintings. A handful of wavering vertical strokes of charcoal inscribe pieces of thick paper torn into irregular shapes, some almost vase-like (Untitled, undated [TD 6628]). It’s easy to imagine that these paper shapes are informed by the bark paintings Tuckson was so familiar with as a curator. Like the barks, they are roughly rectangular but organically skewed. Untitled, c.1970–1973 is a tall piece almost the dimensions of a standing human figure. Here, the charcoal marks are more cumulative and insistent, sweeping the length of the faintly discoloured paper like a life force. This sense of vitality, energy, and urgency permeates the entire exhibition.

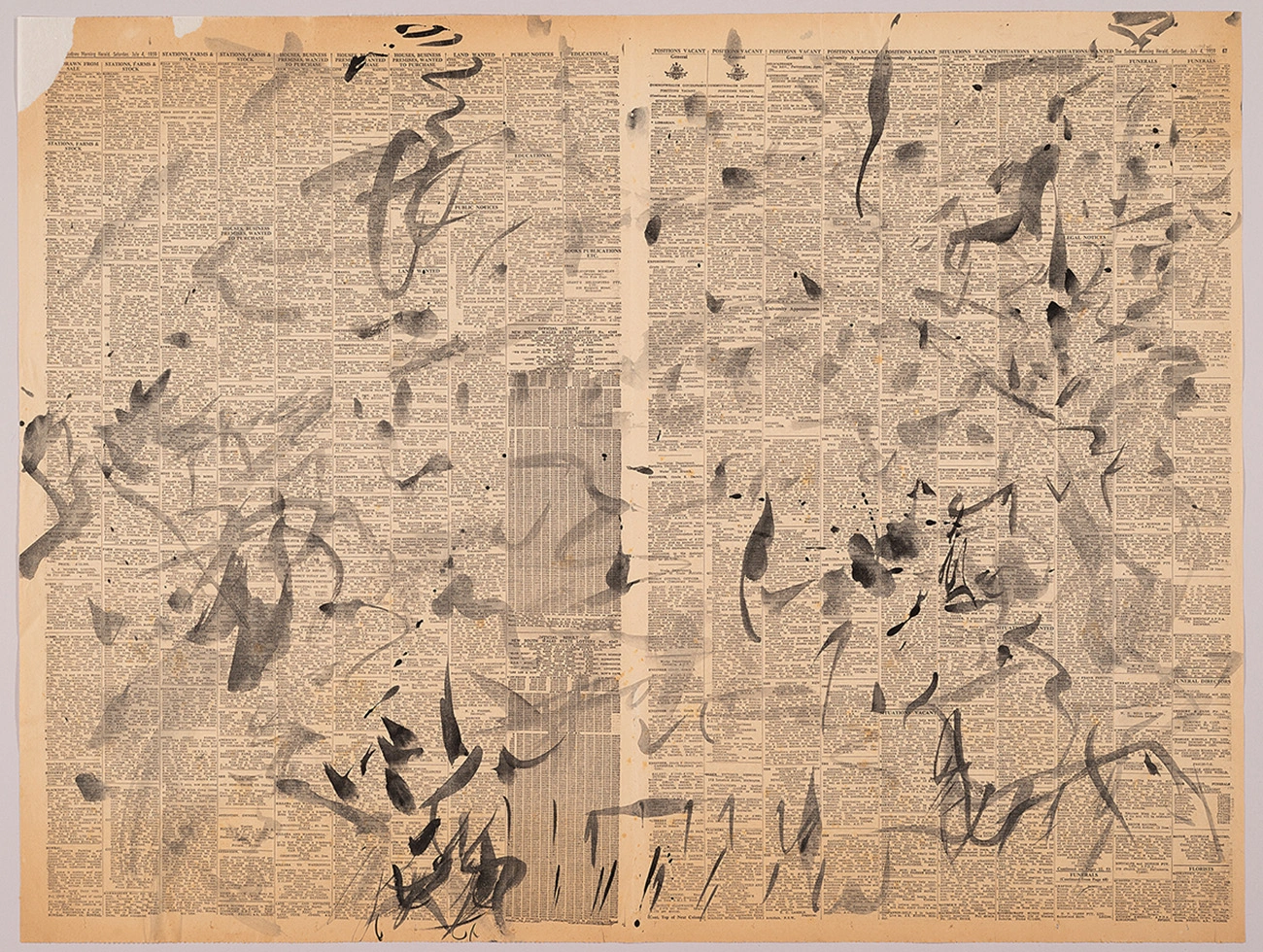

These minimalist drawings contrast with the bulk of the other works, many of which are executed in gouache on newspaper, an archivally unstable material that can also seem abject and ephemeral. Yet, Tuckson produced hundreds of newspaper pieces, suggesting that they sustained and engaged him beyond mere rehearsal. In some examples blots of fluid black paint almost obliterate the newsprint; in another (Untitled, undated [TD 2472]) which Margaret Tuckson put aside for herself in a roll of drawings, restless feathery gestures, dabs, and dashes are dispersed across the surface, transparent here and delicate points of calligraphic blackness there. These pieces indicate how important calligraphy was to Tuckson, as a series of more explicit homages to Chinese characters and ideograms in SYNERGY shows.

In his newspaper works, Tuckson often preferred the classifieds section – the situations vacant and real estate with less obtrusive text than the headlines. He also preferred the yellowish tones of aged paper. These elements provide a textured, light-filled ground for the brushwork, which responds in a process of ‘call and response’ as Oates puts it. In the same way, unprimed masonite provides a warm ground for the paintings.

More radically, Oates proposes that the bi-fold sheets of newspaper with their pale central seams quite possibly informed the diptych format Tuckson came to favour. Once he makes this observation, it’s impossible to unsee it. The organising vertical line between two sheets of masonite in the paintings and the newspaper seams mirror one another.

A handful of well-known paintings such as Pink and White Line [TP70], 1970 lend gravitas to the exhibition. They remind viewers of the lyrical late period when something shifted in the scale of his painting, the expansiveness of his brushwork. They hint at a culminating force, helping visitors to apprehend and appreciate the ‘slighter’ works on paper.

These paintings also prompt the question of how Tuckson arrived at his late transformation. Was it because he finally managed to see his work up, or because he embraced his public persona as artist? Or did he feel intimations of his illness? In an article in The Conversation, Tuckson’s colleague Joanna Mendelssohn describes his face as deeply etched with pain during his final year. Did pain somehow inform his late flowering, or is that too romantic a notion?

‘Tuckson is one of those divisive artists,’ says Maloon. ‘People have been visiting from interstate and rhapsodising. Others have no time for it at all.’ I’m in the rhapsodising camp. I first encountered Tuckson’s work at Maloon’s earlier exhibition Tony Tuckson: Themes and Variations (Heide, 1989). I was still painting then and became obsessed with Untitled (Brown and Grey), 1973, spending several weeks trying to emulate the horizontal brushstrokes, shallow latticework, murky pinks, and bold restraint in his gestures. The same painting is hung here again like an old friend. For me, as with other Tuckson fans, this is a must-see exhibition both to reacquaint oneself with familiar works and to encounter new ones.

And what about for those unfamiliar with his work?

Denise Mimmocchi in Tony Tuckson: The Art of Transformation describes how Tucker once responded to a friend enquiring about a late painting in progress. ‘It’s about this,’ he said referring t0 the curtains in his studio drifting in the breeze. Then he added, gesturing beyond the curtains, ‘And everything out there.’ Through a gap in the fabric, his visitor could glimpse bushland surrounding his Sydney home. But there is nothing pictorial about that painting with its fields of yellow and slit of unprimed masonite, Untitled [TP198a], 1973, held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Tuckson’s comment remains both emphatic and enigmatic. It is worth visiting SYNERGY for some intimation of whatever he meant by everything out there that so compelled him. And for the sheer pleasure of experiencing these works.

SYNERGY: Tony Tuckson – Drawing into painting continues at the Drill Hall Gallery in Canberra until 18 June 2023.

The Drill Hall Gallery acknowledges the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, the traditional custodians of the Canberra region, and recognises their continuous connection to culture, community and Country.

Contact

Close

Subscribe

Close

Close