Stories for Jack Green’s paintings in the ANU Art Collection

Jack Green (Garrwa people) | born Wakaiya Country, Soudan Station, NT, 1953

Ngabaya ngyirridji gunindjba – The Devil that fiddles and digs in our country, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 56 x 61 cm

Gift of private donor, 2021. ANU Art Collection

“The McArthur River region is a powerful place, it’s full of sacred sites that give us life. The red circles represent the sacred sites. At the tail of the Rainbow Serpent rests the Damangani Dreaming, in the top right is the Jerriminni Dreaming. The Garbula tree and the Turtle Dreaming are other sacred sites right at the place where they cut the Snake to create the massive open cut pit in our land when they diverted the McArthur River. After they diverted the river a lot of the senior minggirringi (traditional owners) and junggayi (manager or policeman) for that place died.

The blue circles represent the Dreaming track of another Rainbow Serpent, they show the way he came in before he went down into the ground. That snake’s another powerful ancestral being that can make winds and cyclones.”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2020

Heart of country, 2013

acrylic on canvas, 66 x 84 cm

Purchased, 2014. ANU Art Collection

“The heart represents the life of the country. It’s the heart of Aboriginal people and the country, together, as one. Through the heart runs McArthur River. Rivers are really important places for us. In the middle of the heart are the four clan groups of the Borroloola region. Lined-up are four people sittin’ down. They are the singers. In red are Yanyuwa, black and red Mara, Yellow one Gudanji and brown Garrwa. Above them in the heart are their dancers. It’s though our song and dance that we all pass the knowledge of the country. Above the heart is what the country used to be like. Beautiful, with everything there for us, lots of bush-tucker and water. On the left-hand side at the top are four people. This is the mining company and government. They work together, lookin’ out for each other.

Below them are the drilling rig, grader and dozer belonging to the mining companies who are comin’ into to our country and damaging it with all their machinery. People and bush-tucker get pushed aside having to move somewhere else, sometimes dyin’. You can see the area around the miners is empty— no bush-tucker and no Aboriginal people. No good.

How can Junggayi (Boss for Country) and Minggirringi (Owner of Country) do their job looking after sacred sites when their land, water and food been poisoned?”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2013

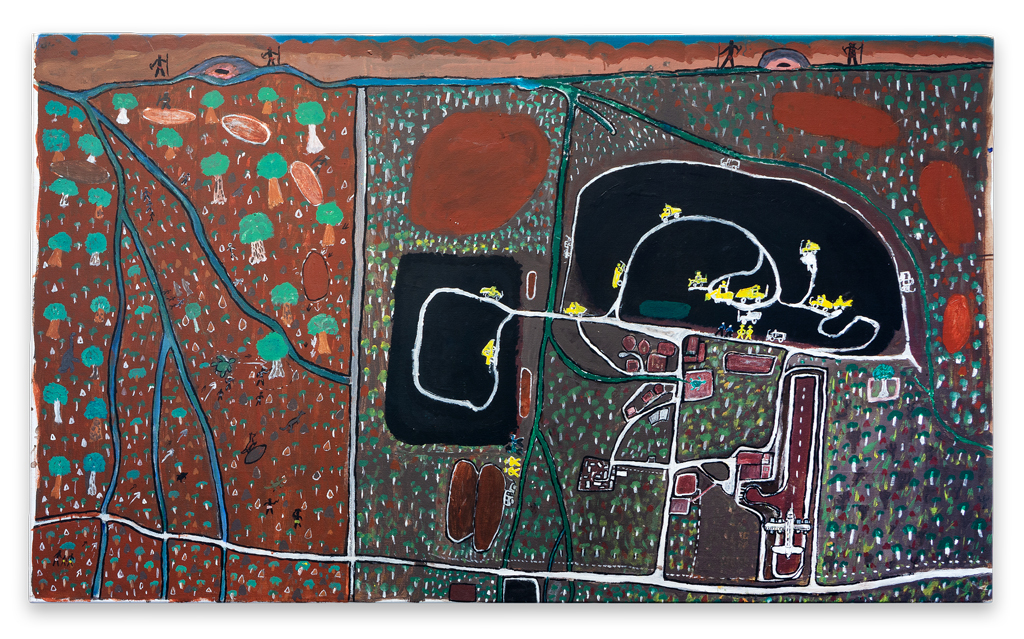

Desecrating the Rainbow Serpent, 2014

acrylic on canvas, 117 x 200 cm

Gift of private donor, 2023. ANU Art Collection

“At the top of the painting, guarded by the Junggayi (Boss for Country) and Minggirringi (Owner of Country), are the eyes of The Rainbow Serpent. The Junggayi and Minggirringi are worried that The Snake is being desecrated. The Rainbow Serpent is one of our spiritually powerful ancestral beings. It rests under McArthur River in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria. Under our Law we hold responsibility for protecting its resting place from disturbance, and responsibility for nurturing its spirit with ceremony and song—just as our ancestors have done for eons. The left of the painting represents a time when we had authority over country. We lived on country, hunted, fished and gathered our food. We used fire to care for country, and most importantly, we protected our sacred places within it. By protecting and nurturing our sacred sites we protect and nurture our spirituality and our wellbeing as Gudanji, Garrwa, Mara and Yanyuwa peoples. The right of the painting represents the present time (2014) when we still have no authority over all of our ancestral country. The artwork illustrates how the resting place of The Rainbow Serpent looks now. It’s been smashed by McArthur River Mine. Country, torn open to make way for one of the largest lead, zinc and silver mines the world has ever seen. To do this they cut the back of our ancestor—The Rainbow Serpent—by severing McArthur River and diverting it through a 5.5 kilometre diversion cut into our country.

A lot of people have died because of the desecration of our sacred places. Interfering with these powerful places, it pulls people down. The stress of seeing our land suffer means we suffer. Men tried to fight but got pulled down. I might be the next one, or the Junggayi will go down. The mining executive might go too. All this pressure, it’s no good.”

Jack Green(Garrwa people), 2014

Sucking the life from our hearts, 2019

acrylic on canvas, 61 x 92 cm

Purchased, 2020. ANU Art Collection

“In the top left sit government people, they far away, making the decision to take our Country and call it Australia. Then come the miners and settlers looking to take over our land. Us Aboriginal people were there ready to spear them to protect our country but they just keep coming, and they still coming today, more and more of them with their drill rigs and mining trucks, diggin’ our scared places, suckin’ the life from Garrwa, Gudanji, Marra and Yanyuwa country making it unsafe for us to hunt and fish and live in our own country.”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2019

How whitefellas look after whitefellas, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 56 x 61 cm

Purchased, 2020. ANU Art Collection

“In the top of the painting are two Whitefellas they represent both sides of politics who direct money into Aboriginal communities. This money doesn’t really go to us Blackfellas it goes to the white dinosaurs that have captured our organisations. They like to look after themselves, make sure they are all good. They like to sit in their offices and make us have to climb up to them. At the bottom of the painting are two more Whitefellas, they been hearing from their mates, ‘Good money to be made in Aboriginal communities’. ‘Beauty,’ they say, ‘get me a job mate’.

All the while we are watching this, even the spirits in the Country are watching, and waiting for things to change.”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2020

Aboriginal Law protects water and people, 2021

acrylic on canvas, 122 x 152 cm

Purchased, 2021. ANU Art Collection

“We can’t live without water. Our rivers are like a mother to everyone, black or white doesn’t matter, without clean water we’ll all be dead. People need it, trees need it, birds need it, cattle need it, even motorcars drink water. When miners and frackers bugger up our rivers and water they put all of us at great risk, doesn’t matter if you’re black or white. Us Garrwa, Gudanji, Marra and Yanyuwa people we have songs for water, songs for the rivers that tell how we all connected. This painting is about how we have to fight to protect our Law to keep our water and our people safe. There are four cultural groups around Borroloola, Garrwa, Gudanji, Marra and Yanyuwa. We each got our own way of making decisions under our Law. Each group talks amongst themselves first, gets as much information as they can and then they make a decision. When they’ve done this, the four cultural groups come together to talk more. The meetings used to happen like this under the big shady trees. Men stand and talk, women stand and talk, people listen and then talk amongst themselves about what they want to do. Government and DAA people used to come into Borroloola and we’d meet them like this as a big group under our Law. But today that doesn’t happen. Government, mining and fracking people just come into town, find a few people and then just throw something down in front of them and say “Here, just take it”. They undermine our Law and won’t let us organise and make sure the right people are at the meeting and the right people are talking for the cultural groups.

When they do this to us it not only weakens our Law and undermines our rights as Aboriginal people, but it means we can’t protect our rivers and our water and keep our people safe. Government does this to us so they can give our water for free to miners and frackers who bugger it up. When they done this, they just run away to where they came from with all the money, they made from using our water and they leave nothing for us and our kids, nothing for our future.”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2021

Four Clans – all their sacred songs, all their sacred dances, 2021

acrylic on canvas, 61 x 61 cm

Gift of private donor, 2022. ANU Art Collection

“There are four main clan groups around Borroloola – Yanyuwa and Marra, saltwater people from the coast and islands. Gudanji and Garrwa, fresh water people from the mainlands and river flats.

It has been like this forever – right back to the Dreamtime – we are part of this country and we are all part of the sacred song lines, the stories in the land, the ancestor places and the spirit people that are in these places. We call out to them and we hear their voices. Our people tell stories and connect to our ancestors and our country through song and dance. We also write new songs and dances when we want to talk about something that has happened not so long ago.

In this painting I am talking about scared country and the song and dance of all our four clans. Garrwa people telling the story of Little Eva with their Aeroplane Dance, Gudanji dancing a sacred Mermaid song, Marra doing the Buffalo dance and Yanyuwa coming up with something new…”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2021

My life, so far, 2022

acrylic on canvas, 51 x 122 cm.

Gift of private donor, 2022. ANU Art Collection

“In the top left of the painting is Soudan Station in the Northern Territory. You got the station manager’s place with the fence around it and then the old pink corrugated iron shed, with a few trees around it. That’s the place my family lived when they worked there. At the station, there’s an old creek running near our place. An Old Devil Devil, we call Irinju lives there, under the ground. The Old Devil, he used to throw his hand up out of the creek and steal the wild oranges from the tree that grew nearby. The old people tried to stop him and one night cut his hand off at the wrist with a stone axe when he was stealing the fruit. When this happened he wildly pulled what was left of his arm back into the ground. His arm flapped about and this is what made the twisting creek bed.

I was born right there in the elbow of the creek, right where old Irinju lives. When my mother gave birth to me under the shade of the coolabah tree the Aboriginal midwives held me up and I was covered in hair. Lots of this black hair, just like Irinju. My father wanted to kill me as he thought my mother had given birth to the Old Devil Devil. The midwives had to argue with my father, tell him to go away and that everything was alright. Later on my father could see that I wasn’t Irinju. He was good to me and taught me when I was young how to ride horses, hunt goanna and live in the bush.

When I was about 14 my father put me through ceremony, at Walhallow on the Barkly Tablelands, to make me a man. A part of this ceremony is that me and another young fella going through with me had to go out into the bush for a period of time by ourselves to learn how to live. When we came back and the ceremony finished we were men.

After this, I went to work as a young fella on the pastoral stations around the NT. There was no school for us Aboriginal kids, just work. Over this time I learnt from the old people about the Country, the sacred sites, the Dreaming tracks and all our stories. I learnt more about hunting, how to catch animals, prepare them to eat and how to share them with others. I also learnt all about cattle. I worked on a lot of stations over this time; Cresswell; Anthony Lagoon; Banka Banka; Mungabroom; Eva Downs; and Ucharondige. I went across to Hayfield near Larrimah, then up to Innesvale Station near Katherine before I worked my way back to Borroloola where I worked on the Aboriginal Night Patrol for the Resource Centre with Rex Hume.

It was at this time, in 1988, that senior Aboriginal people from the four clans in Borroloola chose me to be trained as a Field Officer for the Northern Land Council. I worked for the NLC close to 40 years. First on land claims, then later I set up the Garrwa and Waanyi Garrwa Rangers to help people look after their Country and have meaningful work. I also helped Waanyi and Garrwa people establish an Indigenous Protected Area in the Nicholson River region of the NT. This was important, we worked with a a lot of families in Doomadgee, Mt Isa, Tennant Creek, Borroloola, Katherine and Darwin. People got pushed far away from their Country and it was important to help them come together to care for their Country.

Today, it’s 2022 and I’m living in Borroloola. I’m one of the senior elders of Borroloola. I was a board member of the Aboriginal Area Protection Authority for a few years fighting to protect the sacred sites near McArthur River Mine. I’m also a council member on the Full Council of the NLC. Borroloola people have supported the NLC for a long time, sometimes we feel like the NLC forgets how our customary decision-making works. I still work as a senior cultural advisor for the rangers working at Robinson River and the Nicholson. I paint, stories of our Country and our long fight to protect and care for the sacred sites, Dreaming Tracks, plants, animals and water. I fight so that our young people can have good lives as Aboriginal people.”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2022

No blacks allowed, 2019

acrylic on canvas, 41 x 41 cm

Purchased, 2020. ANU Art Collection

“Government been working for a long time to push us Aboriginal people off our homelands. Many people end up in town with no job, no house and no family support. Being in town, whether it be Darwin, Katherine or Tennant Creek can be dangerous for Aboriginal people.

Aboriginal people are always getting moved along, always watched, always told you can’t be here.

Once when people were drinking they could sit in the park, under the trees out in the open where they could be seen and feel safe. But these days Aboriginal people aren’t allowed in the parks when they drink. The parks are for white people, they like to keep them nice and green.

Being pushed out of these places makes it unsafe for Aboriginal who can’t drink in a hotel, kept out because of no shoes or because the bouncer doesn’t like the look of ya.

People are pushed into the scrub to drink. They pushed out where no one can see them. It’s not safe drinking on the side of the creek where a croc might get you or at place where you might get murdered.

Government and councils don’t care about making it safe for Aboriginal people as long as their green parks look good for white people.”

Jack Green (Garrwa people), 2019

The Drill Hall Gallery acknowledges the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, the traditional custodians of the Canberra region, and recognises their continuous connection to culture, community and Country.

Contact

Close

Subscribe

Close

Close